Judge – First Instance Court of Turin

(Italy)

Member of the “Groupe de pilotage”

of the CEPEJ SATURN Centre of the Council of Europe

Enquiry

into the

“Customer

Satisfaction Survey in Turin Courts”

|

Table of Contents: 1. Introductory Remarks. The

Turin Survey in the Framework of the Initiatives of the European Commission

for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) of the Council of Europe. – 2. Working Group and Timeframes. – 3.

Methodology, Object and Target of Turin Survey. – 4.

The Overall Impact and the Importance Given by Users to Various Items of

Provided Services. – 5. Outcome of the Survey:

Staff, Judges, Timeframes and Costs of Justice. – 6.

Overall Outcome of the Survey: Satisfaction and Importance. |

1. Introductory Remarks. The Turin Survey in the Framework

of the Initiatives of the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) of the Council of Europe.

The

“Customer Satisfaction Survey in Turin Courts” belongs to the

cooperative activities that the Turin First

Instance Court (Tribunale di Torino)

carries out in its capacity as a member of the di Pilot Courts Network of the CEPEJ (Commission Européenne

pour l’efficacité de la justice/European Commission for the

Efficiency of Justice) of the Council of Europe. The initiative draws its

origin from the activities of the Working Group on the quality

of justice of the CEPEJ (CEPEJ-GT-QUAL). This panel (also on the

basis of previous experiences realized at the Court of Geneva) has recently

edited a Report on “Conducting Satisfaction Surveys of Court Users in

Council of Europe Member States.” This handbook, available on the Council

of Europe’s web site, together with other documents which have been

drafted by the same organ, contains as well a “Model Questionnaire for

Court Users,” which can be used, with the appropriate adjustments, in

each and every Judicial Office willing to test the level of satisfaction of

people who, for any possible reason, contact such bodies.

Setting

up criteria and directives for the realization of surveys of this kind lies

within the fundamental scope of the CEPEJ,

that are the improvement of the efficiency and functioning of justice in member

States, and the development of the implementation of the instruments adopted by

the Council of Europe to this end. In order to carry out these different tasks,

the CEPEJ prepares benchmarks,

collects and analyses data, defines instruments of measure and means of

evaluation, adopts documents (reports, advices, guidelines, action plans,

etc.), develops contacts with qualified personalities, non-governmental

organisations, research institutes and information centres, organises hearings,

promotes networks of legal professionals.

Amongst

the working groups of CEPEJ, besides

the already mentioned panel on the themes of the quality of justice, we can

also mention the Groupe de Pilotage

of the “Centre for judicial time management (SATURN Centre – Study

and Analysis of judicial Time Use Research Network).” The SATURN Centre

is instructed to collect information necessary for the knowledge of judicial

timeframes in the member States and detailed enough to enable member states to

implement policies aiming to prevent violations of the right to a fair trial

within a reasonable time protected by Article 6 of the European Convention on

Human Rights. It should also be added that CEPEJ

set up a Network of Pilot-courts from European States to support its activities

through a better understanding of the day to day functioning of courts and to

highlight best practices which could be presented to policy makers in European

States in order to improve the efficiency of judicial systems.

2. Working Group and Timeframes.

The

idea of running a satisfaction survey in Italy aimed at Court users is founded

upon the above mentioned guidelines prepared by the Quality Working Group of

the CEPEJ. The concrete input came at

the end of 2010 by the Director-General of Statistics of the Italian Department

of Justice, who invited the two Italian members of the Network of Pilot Courts,

which to say the First Instance Court of Turin and the Appeals Court of

Catania, to run a survey on the degree of customer satisfaction; the initiative

has also been extended to the Appeal Court of Turin, whose President, former

President of the local First Instance Court, Dr. Mario Barbuto, is the author

of the “Strasbourg Programme,” which, in the year 2001, constituted

the first concrete experiment of case management in Italy. Actually, it is due

to this programme that in 2006 the Turin First Instance Court was awarded by

the Council of Europe and the European Union a special mention in the framework

of the “The Crystal Scales of Justice Award.”

A

working group was therefore set up, under the coordination of the

Director-General of Statistics of the Italian Ministry of Justice (DGStat), Dr.

Fabio Bartolomeo. The panel comprised also, as

far as the Turinese section was concerned, the President of the Appeals Court

of Turin, Dr. Mario Barbuto, the President of the First Instance Court of

Turin, Dr. Luciano Panzani, as well as Dr. Brunella Rosso, President of a

Section of the Appeals Court of Turin, Dr. Giacomo Oberto, Judge of the First

Instance Court of Turin, Dr. Roberto Calabrese, statistical expert of the

Appeals Court of Turin and Dr. Luigi Cipollini, statistical expert of the DGStat.

The working group was also comprised of the President of the Turin Bar, Avv.

Mario Napoli, as well as by the representatives of the Observatory on Civil

Justice of Turin, Avv. Raffaella Garimanno and Avv. Angelica Scozia, by Prof.

Eugenio Dalmotto, of the Law Faculty of the University of Turin, and by the

person in charge of organisation of decentralised training for judges in the

Turin District of the Appeals Court, Dr. Ombretta Salvetti, Judge of the First

Instance Court of Turin. The group was charged with defining the aims of the

survey, to single out the targets and to draft the questionnaire. Moreover it

has monitored the correct implementation of the survey and is currently

ensuring the distribution of its results.

In

its first meetings the aforementioned working group had proceeded towards the

drafting of the questionnaire, along the lines of CEPEJ guidelines, however introducing some adaptations to the

Italian reality. Therefore it contacted the Law Faculty of the University of

Turin and in particular Prof. Eugenio Dalmotto, Professor of Civil Procedural

Law, who organized and made available a group of approximately 25 students.

These people materially carried out the survey, spreading the questionnaire and

gathering answers to it. In view of developing this activity, the working group

held some preparatory meetings with the students, in order to train them to run

the survey questionnaire and illustrate the scope and modality of surveying. It

has also to be added that the rigorous timeframes set in the first meeting of

the working group, which was held at the Ministry, in Dr. Bartolomeo’s

office, on 12th October 2010, have been fully complied with. So the

questionnaire was finalised by the end of November 2010; after this the

initiative was explained to the aforementioned group of students, who were

appropriately trained between December 2010 and January 2011. Interviews of

customers were conducted with the delivering of 618 questionnaires in the

period between January and March 2011. After each interview, conducted by a

student on the basis of the questionnaire, answers provided were verified and

inserted via the web in the appropriate data bases; final data was analysed and

elaborated in the framework of a conclusive report.

3. Methodology, Object and Target of Turin Survey.

Coming

now to illustrate the object of the Turin survey, it must be said that the

working group decided in the first place to single out the judicial offices in

which customer satisfaction should be measured. For this purpose the panel

decided to choose the First Instance Court and the Appeals Court of Turin,

having regard to both civil and penal sectors. Prosecution offices before said

Courts were excluded, as well as, for logistical reasons, the Juvenile Court,

the Offices of the Justice of the Peace and the four Detached Sections (i.e.:

sections pertaining to other cities situated within the boundaries of Turin

district) of the First Instance Court. This was expressed in question No. 1 of

the questionnaire (Q.1); replies are condensed in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1 – Courts serving interviewees.

Diagram

1 shows that 93% of the interviewed people were served by the Court of First

Instance (Tribunale), whereas the

remaining 7% to the Appeals Court (Corte

d’Appello). This percentage roughly reflects the existing ratio

between the total number of cases lodged with the First Instance Courts of the

District and cases pending before the Appeals Court.

As

far as the target of the survey is concerned, the above mentioned panel

decided, at least for this first experiment, not to involve practitioners.

Therefore the questionnaire was not addressed to judges, lawyers, trainee

lawyers, Court clerks and other employees of the justice administration system.

It was decided instead to focus on parties, witnesses, jurors, relatives of

parties or witnesses, Court’s or party’s experts, interpreters. The

reason of such decision is that practitioners like judges, prosecutors,

magistrates, lawyers and employees of the administration of justice already

dispose of institutions (associations, bar and professional organisations,

trade unions, etc.) which may bring to the outside world impressions, needs and

“moods” of such professionals of justice.

Scope

of the survey, in its various articulations, was to provide a general idea on

following three fundamental aspects: a) expectations, b) importance of services

and c) satisfaction and perception about rendered services. Diagram 2 shows

overall data breakdown by various categories of users.

Diagram 2 – Data breakdown by various categories of

users.

Diagram 2 – Data breakdown by various categories of

users.

Diagram

2 shows that a high number of people visiting the Turin Palace of justice were

in the category of parties in a lawsuit. In particular, the figure referred to

the relatives of a party and to the spectators, whose two percentages reach a

total figure of 20%, was surprisingly high.

Collected

data shows that interviewed people were predominantly male, of almost all ages;

such people were in their majority married; they had (at least) an advanced

secondary school certificate and a full time job. The majority of full time

employed people are civil servants and private enterprise employees, followed

by freelancers, workers, entrepreneurs and independent workers. The majority of

interviewed people have shown to be able to orient themselves in judicial

offices, without previously collecting information by phone or in another way,

as it is illustrated in Diagram 3.

Diagram 3 – Information gathered by customers prior to visiting

a Court.

Data

gathered from the answers to the survey shows that the overwhelming majority of

customers either did not try to get information by phone, email or on the Web

Site, or they said they did not need to gather information. However, it is

important to point out that, out of the 14% of the customers who tried to get

information, the vast majority (80%) succeeded in their quest.

Other meaningful information is supplied by the

breakdown of categories of procedures, as illustrated by Diagram 4.

Diagram 4 – Breakdown categories of procedures involved.

Diagram 4 – Breakdown categories of procedures involved.

Percentages

referred to in Diagram 4 show, as expected, a preponderant involvement of

interviewed people in penal procedures, whereas in civil procedures those areas

of law prevailing are (in decreasing order) family law, torts, enforcement

matters and labour cases.

A

further element allowing a better knowledge of users’ needs concerns the

number of times interviewed users have visited Turin judicial offices, as illustrated

in Diagram 5.

Diagram 5 – Number of times interviewed users have been

visiting Turin judicial offices.

Diagram 5 – Number of times interviewed users have been

visiting Turin judicial offices.

Data

shown in Diagram 5 turn out to be rather unexpected. Actually, the total number

of those people who visited such offices more than once exceeds by far the

figure of those people who were visiting Turin judicial offices for their first

time. Quite remarkable are data concerning people who have been visiting the

palace of justice five or more times (27%): this seems to show the existence of

a category of “frequent visitors” of judicial offices.

4. The Overall Impact and the Importance Given by Users

to Various Items of Provided Services.

Diagram 6 records what could be defined as “the

overall impact:” the general impression customers get about services

provided by Turin judicial offices.

Diagram 6 – General impression customers get about

services provided by Turin judicial offices.

Diagram 6 – General impression customers get about

services provided by Turin judicial offices.

General

data can be seen as rather reassuring, as it turns out that the sum of those

who declared themselves very much satisfied and of those who declared

themselves enough satisfied reaches the threshold of 50%, while the total

number of people who declare themselves less than (or not at all) satisfied is

less than one third of the total. It is obvious that a lot still remains to be

done, as is made clear, in particular, by the empirical data portrayed in

Diagram 8d.

Data

summarised in Diagram 7 is of great interest, as it refers to the importance

customers attach to various characteristics of services offered.

Diagram 7 – Importance given to various elements of

services offered.

Diagram 7 – Importance given to various elements of

services offered.

Amongst

all the elements which appear essential for the customers’ judgment, one

of the most relevant is the competence of judges (35%). Users declared to

prefer such item, although slightly, to the fairness of judgment (31%). We find

rather distanced, notably, data on the duration of procedures (18%); finally,

the weight accorded to kindness/politeness of judges and of the staff was

almost insignificant (12%), as well as the comfort of judicial premises (5%).

Such information allows us to adequately assess and “calibrate”

data emerging from Diagrams 8b, 8c and 8d.

Some

other elements allowing us to assess general impact concern the logistics of

judicial services: particularly premises (location, comfort, cleanness, clarity

of signage within the courthouse) and working hours, as illustrated in Diagram

8a.

Diagram 8a – Assessing the logistics: premises and working

hours.

Diagram 8a – Assessing the logistics: premises and working

hours.

The

overall judgment on the above mentioned results on evidence concerning

logistical aspects of Turin’s Justice Palace, and to the services

supplied there, appears more than gratifying. The sum of the percentages of

those who declared themselves fully or rather in agreement with the appraisal

in positive terms on feasibility, cleanliness and comfort of the premises,

clarity of signage within the courthouse and convenience of working times,

reaches a total number of people who almost always exceed two thirds of the

total of interviewed people, while the relative “level of dissatisfaction”

(which is comprised of the percentages of those who declared themselves

partially or not at all in agreement) is always between 5% and 18%.

5. Outcome of the Survey: Staff, Judges, Timeframes and

Costs of Justice.

The

most important and interesting part of the questionnaire relates to a series of

elements that, in the process of drawing up the questionnaire, the working

group thought indispensable for an accurate assessment of services offered to

users. Therefore the panel decided to put the focus, in the first place, on

such elements as: easy recognisability, competence, availability and clarity of

the staff, as it is shown in Diagram 8b.

Diagram 8b – Assessing

the staff.

Diagram 8b – Assessing

the staff.

Apart

from the item of staff’s easy recognisability and the availability of

information on the Internet and other sources of information, other questions

related to the clerical staff indicate a high level of satisfaction. Therefore,

the number of those people who declared themselves as rather or fully agreeing

on items such as the competence of the staff, their availability to help

customers and to provide clear information, exceeds half of the interviewed

people, while the degree of dissatisfaction is around 10%.

Coming now to the judges, the idea has been to focus

attention on elements such as their capability to inspire trust and confidence,

their competence, impartiality, politeness and the ability to express

themselves with clarity, as it is shown in Diagram 8c.

Diagram 8c – Assessing

the judges.

Diagram 8c – Assessing

the judges.

Data

relating to the assessment of the judges is decidedly comforting. The overall

level of satisfaction (that is the sum of data of those who

declared themselves rather in agreement and of those who said they fully agreed

with the assertion that judges inspire trust and confidence, that they are

competent, impartial, polite, and that they are able to express themselves with

clarity) is always higher than 50%. Relative percentages of dissatisfaction oscillate

instead between 14 and 22%. Such results seem rather surprising, especially

when we think of the campaign of systematic denigration and delegittimation of

the judiciary, which is currently present in Italy. The data appears all the

more comforting, if we note that the level of importance attributed to the

above mentioned items is the highest which has been registered (see above,

Diagram 7 and relative comments).

Coming,

finally, to the assessment of time and cost, the working group decided to ask

questions concerning: fairness of costs for litigation, reasonableness of

timeframes, punctuality of hearings, overall organization of the judicial

office and the possibility to obtain information easily, as it is shown in

Diagram 8d.

Diagram 8d –

Assessing timeframes and costs of justice.

Diagram 8d –

Assessing timeframes and costs of justice.

Diagram

8d is unique in providing alarming evidence on the current situation of the

system. Customers’ assessment about reasonableness of judicial timeframes

is merciless: actually, the level of dissatisfaction reaches 75%, against 13%

of those who declared themselves rather or fully in agreement with the

assertion that the reasonable duration of the procedures is concretely assured.

Such an outcome is astonishing, in the light of the positive results of the

“Strasbourg Programme” (that allowed the Turin First Instance Court

to achieve far better results than those of the other Italian courts). However,

such a shortcoming can be at least in part mitigated by the fact that the level

of importance that customers attach to the reasonable duration of process

appears remarkably inferior to the one attributed to the competence of judges

(see above, Diagram 8c). Data mentioned above can perhaps be explained in the

light of the fact that the survey also comprises criminal trials and that,

whereas the whole civil process is managed by the Court, the criminal trial is

managed by two different offices: the Public Prosecutor’s Office in the

first place and the Court in the second place. Therefore we have also to take

into account possible delays in the Public Prosecution Office. A surprising

weak spot, at least as far as Turin is concerned, is constituted also by data

concerning punctuality of hearings (46% of people declared themselves

unsatisfied, against 39% who declared themselves satisfied); this outcome can

be explained with regard to the fact that the majority of interviewed people

were involved in penal proceedings, and for such hearings (unlike civil

hearings) no system of staggering is in use.

No

surprise comes from data on the assessment of judicial costs, which are deemed

as not fair by 53% and fair by 25% of interviewed people. On the contrary, data

on the overall organisation of judicial office appears comforting (61% of

interviewed people declared themselves satisfied, against 19%, who declared

themselves unsatisfied); the same is true for data concerning availability of

information (61% satisfied, against 21% unsatisfied).

6. Overall Outcome of the Survey: Satisfaction and

Importance.

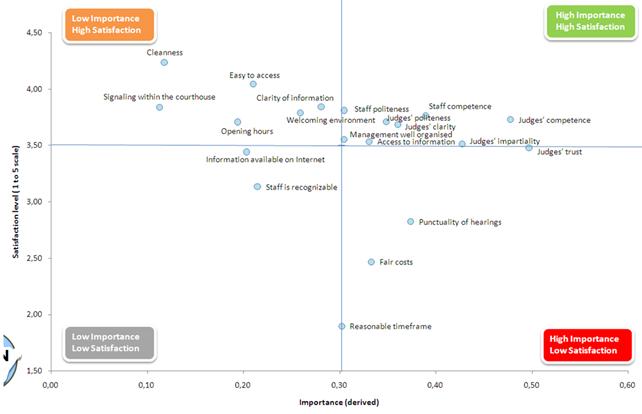

The

empirical data gathered by the survey can be represented graphically by

cross-referencing the replies of interviewed people on issues pertaining to

satisfaction about services rendered by Turin judicial institutions with

replies on the various characteristics (items) considered as regards their

importance. In this graph (see Figure 1) it is possible to determine four

distinct areas. Such areas are defined by drawing two lines across, on the

points of the two axes (abscissae and ordinates) matching respective average

values. Data concerning “importance” was statistically derived

using the Spearman correlation index between each specific item and the overall

satisfaction. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is a non-parametric

measure of statistical dependence between two variables. It assesses how well

the relationship between two variables can be described using a monotonic

function, either always increasing or always decreasing.

Items

falling within the square situated in the upper-right part of the map are those

which are considered as important by users and that at the same time received a

high satisfaction score. This explains why we could define this area as an

“Area of Excellence,” (“High Importance-High

Satisfaction”), to be constantly monitored and valued in the interest of

a better service to the citizens. A high importance (above the average),

associated to a low degree of satisfaction (under the average), characterizes

the area situated in the lower-right part of the diagram, that is the area of

the “needs which are not adequately satisfied,” or “Area for

Improvement” (“High Importance-Low Satisfaction”). The items

of this part of the map require a great deal of attention.

A low

degree of importance associated to an elevated degree of satisfaction characterizes

those items which, in spite of a positive assessment by the customers, are not

perceived as essential. Therefore, for these items keeping the same level of

quality can be deemed sufficient (see the upper-left area of the diagram, which

could be called “Area for Maintenance”: “Low Importance-High

Satisfaction”). Finally, relatively negligible are those items which,

although characterised by a low level of satisfaction, are considered by

customers as less important than others (see the lower-left area of the

diagram, which could be called our “Area of Indifference”:

“Low Importance-Low Satisfaction”).

It

must be noted that in the “Area of Excellence” we can find nearly

all the items related to politeness, competence, clarity and impartiality of

the judges, a couple of items pertaining to the staff (competence and

availability), as well as the good organization of the offices and to the

easiness to gather information.

|

|

Figure 1 – Satisfaction vs. Importance

Diagram.