Chair

of the “CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time Management”

Turin

Court

Secretary

General of International Association of Judges

Judicial

Time Management –

Tools

Developed by CEPEJ SATURN Centre

to

Prevent Violations of Article 6 of ECHR

![]()

|

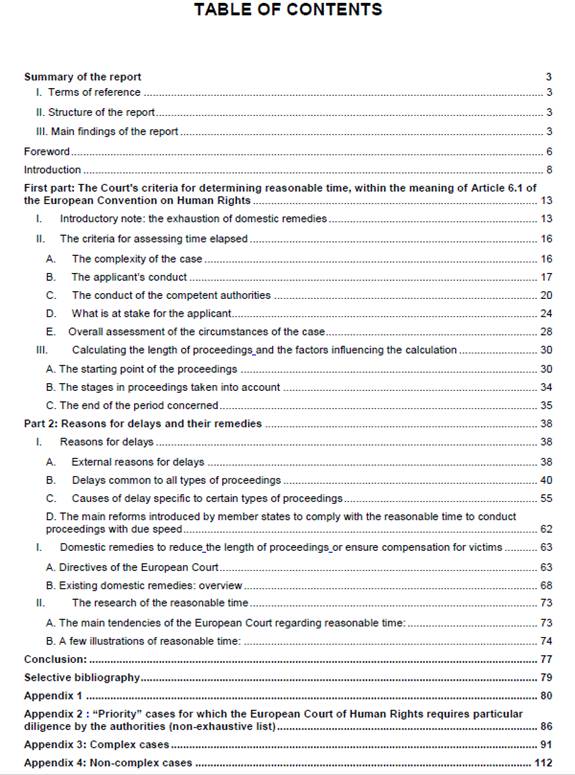

Table Of Contents: 1. Introduction. The Waking Up of the Awareness on Case

Management in Europe. – 2. The CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time

Management: Terms of Reference and Composition. – 3. Main Tools

Adopted by the CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time Management: The “Saturn

Guidelines for Judicial Time Management”. – 4. Main Tools Adopted by the CEPEJ SATURN Centre for

Judicial Time Management: The Implementation Guide “Towards European

timeframes for Judicial Proceedings”. – 5. Other Tools and Main Studies on Judicial Time

Management. – 6. On-going Works

within the CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time Management. New Approaches

and Tools on Case Management in Europe: Case Weighting. – 7. On-going Works

within the CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time Management. New Approaches

and Tools on Case Management in Europe: Dashboards for Court Management. |

1. Introduction.

The Waking Up of the Awareness on Case Management in Europe.

The setting up at

the end of the year 2002,

within the Council of Europe, of the European Commission for the Efficiency of

Justice (Commission Europenne pour

l’efficacité de la justice – CEPEJ: http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/cooperation/cepej/presentation/cepej_en.asp)

marks the dawn of a new era, characterised by the waking up of the awareness about the need for efficiency and case management in our

continent.

Objectives of the CEPEJ, which is made up of

representatives of the 47 member states of the Council of Europe, are the

following missions:

• to propose to the States

pragmatic solutions as regards judicial organisation, taking fully into account court users,

• to enable a

better implementation

of the Council of Europe’s

standards in the justice field,

• to contribute

toward relieving

the case-load of

the European Court of

Human Rights by providing states with effective solutions to prevent violations of the right

to a fair trial within a reasonable time (Article 6 of the European Convention of Human

Rights).

Among the main activities of the

CEPEJ we may mention the development of concrete measures and tools aimed at policy makers and

judicial practitioners in order to:

• analyse the functioning

of judicial systems and orientate public policies of justice: the CEPEJ has set

up a continuous evaluation

process of the functioning of judicial systems in all the European

states, on a comparative

basis. This unique process in Europe enables, through the collection of

quantitative and qualitative data, to have a detailed photography of the

functioning of justice and to measure its evolution. This tool for in-depth

analysis enables to orientate public policies of justice.

• have a better

knowledge of judicial

timeframes and optimize

judicial time management:

CEPEJ has been developing practical tools aimed at professionals for a better

knowledge and improvement of the situation of judicial timeframes and time

management in courts in the European States, as well as concrete tools aimed at

professionals (Compendium of best practices, Judicial time management

Checklist).

• promote the quality

of the public service of justice: beyond the efficiency of judicial

systems, the CEPEJ aims to identify the elements which constitute the quality

of the service provided to users in order to improve it and aims to develop

innovative measures (Checklist

for promoting the quality of justice and the courts, Handbook for conducting satisfaction surveys

aimed at court users, European

ethical Charter on the use of Artificial Intelligence in judicial

systems and their environment).

• promote the use of mediation through member

States, conducting studies on the impact of the Committee of Ministers’

Recommendations concerning family mediation, mediation in criminal matters,

alternatives to litigation between administrative authorities and private

parties and mediation in civil matters, as well as drawing up guidelines in these areas

as well as specific measures to ensure effective implementation of these

recommendations.

• support

member states in their reforms of court organisation: the CEPEJ is entrusted with

giving targeted cooperation

to the states which request it in the framework of their institutional and

legislative reforms and for organising their justice system.

• get the users closer to their justice system:

the CEPEJ is at the initiative, together with the European Commission in

Brussels, of the European

Day of Justice. It has been celebrated each year on 25 October and

enables the public, through various events organised by judicial institutions

in the European states, to get better acquainted with their justice system and

its functioning. Within the framework of this Day, a European Prize: “The

Crystal Scales of Justice” has been created in 2005, aimed at

highlighting innovative and effective practices carried out within courts to

improve the functioning of justice.

• creating and

maintaining a network

of pilot courts from European States to: a) support its activities

through a better understanding of the day to day functioning of courts and b)

to highlight best practices which could be presented to policy makers in

European States in order to improve the efficiency of judicial systems.

Therefore, the Network is:

o

a forum of information: Pilot courts are privileged addressees of the information

on the work and achievements of the CEPEJ and are invited to disseminate this

information within their national networks. Within the Network, Pilot courts

communicate and cooperate.

o

a forum of reflection: The Network is consulted on the various issues

addressed by the CEPEJ.

o

a forum of implementation: some Pilot courts can be proposed to trial at

local level some specific measures proposed by the CEPEJ.

2. The CEPEJ SATURN

Centre for Judicial Time Management: Terms of Reference and Composition.

The CEPEJ SATURN (Study and

Analysis of judicial Time Use Research Network) Centre has been set up in 2007 by CEPEJ as a Centre

for judicial time management. According to its terms of reference the

SATURN Centre is instructed to collect information necessary for the knowledge of judicial timeframes

in the member States and detailed enough to enable member states to implement

policies aiming to prevent violations of the right for a fair trial within a

reasonable time protected by Article 6 of the European Convention on Human

Rights.

The Centre is aimed

to become progressively a genuine European observatory of judicial timeframes,

by analysing the situation of existing timeframes in the member States

(timeframes per types of cases, waiting times in the proceedings, etc.),

providing them knowledge and analytical tools of judicial timeframes of

proceedings. It is also in charge of the promotion and assessment of the

Guidelines for judicial time management.

The Centre is managed through a

Steering group, established in accordance with article 7.2.b of Appendix

1 to Resolution

Res(2002)12, under the authority of the CEPEJ. The Steering group works in

particular for collecting, processing and analysing the relevant information on

judicial timeframes in a representative sample of courts in the member states by

relying on the network of pilot courts. Thus, it must define and improve

measuring systems and common indicators on judicial timeframes in all member

states and develop appropriate modalities and tools for collecting information

through statistical analysis. (Further information on CEPEJ-SATURN available

here: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cepej/cepej-work/saturn-centre-for-judicial-time-management).

According to its Terms of reference, in

order to implement the “Strategic plan for the

SATURN Centre” (CEPEJ-SATURN(2011)5), the Steering group shall in

particular:

·

periodically collect data on procedural times in

member States at national and regional level, for all types of proceedings (civil, criminal and

administrative) and for all

courts (first instance, appeal and supreme courts);

·

verify the completeness

and quality of the data

collected in order to make improvements;

·

analyse the data collected and

collate them with the principles relating to procedural times derived from the

case law of the European Court of Human Rights;

·

define

guidelines and standards

relating to procedural

times:

o

for all state organs concerned with justice:

legislators, bodies vested with the administration of justice, court managers,

judges, prosecutors, police officers;

o

for all types of proceedings (civil, criminal and

administrative);

o

for all courts (first instance, appeal and supreme

courts);

·

disseminate in member States

the guidelines, the

standards and the results of analysis of

the data collected;

·

promote the use of judicial time management tools,

particularly those developed by the SATURN Centre, in all member States to

enable them to make their own analysis of the situation regarding judicial

timeframes in their courts and apply their own remedies to any excessive

procedural delays;

·

undertake within the member States most concerned by

questions of procedural delays, and with their agreement, targeted actions to

improve their situation (preventive or proactive measures) by implementing

judicial time management tools in those countries;

·

rely on

appropriate networks allowing the integration in the work and considerations of the judicial

community, in particular on the network of pilot courts within the member

States, to draw on innovative projects aimed at reducing and adjusting the

timeframes operated by courts in member States;

·

organise and implement the court coaching programme

(on a volunteer basis) for the effective use of the CEPEJ’s tools and

guidelines, on the basis of the relevant SATURN Handbook (CEPEJ-SATURN

(2011)9).

|

Current

Composition of

the SATURN Steering Group: |

|||

|

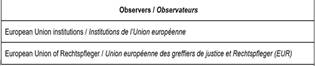

Among the main

activities done and tools adopted by the CEPEJ SATURN Centre we can mention

first of all the “Saturn guidelines for judicial time management” (see:

https://rm.coe.int/cepej-2018-20-e-cepej-saturn-guidelines-time-management-3rd-revision/16808ff3ee),

whose main aim is to reduce the length of judicial proceedings.

Particularly

relevant are the guidelines enshrined in the part (II) dedicated to legislators

and policy makers, such as the following:

|

II. C. Substantive law 1. Legislation

should be clear, simple, in plain language and not too difficult to

implement. Changes in substantive law should be well prepared. 2. When enacting

new legislation, the government should always study its impact on the volume of new cases and avoid rules and regulations

that may generate backlogs and delays. 3. Both the users

and the judicial bodies should be informed in advance about changes in

legislation, so that they can implement them in a timely and efficient way. II. D. Procedure 1. The rules of

judicial procedures should enable compliance with optimum timeframes. Rules

that unnecessarily delay the proceedings or provide for overly complex

procedures should be eliminated or amended. 2. The rules of

judicial procedure should take into account the applicable Recommendations of the Council of Europe,

in particular the Recommendations: R (81)7 on

measures facilitating access to justice, R (84)5 on the

principle of civil procedure designed to improve the functioning of justice, R (86)12

concerning measures to prevent

and reduce the excessive workload in the courts, R (87)18

concerning the simplification of criminal justice, R (95)5

concerning the introduction and improvement of the functioning of appeal

systems and procedures in civil and commercial cases, R (95)12 on the

management of criminal justice, R (2001)3 on the

delivery of court and other legal services to the citizen through the use of

new technologies. 3. In drafting or amending the procedural

rules, due regard

should be had to the opinion

of those who will apply

these procedures. 4. The procedure

in the first instance should promote expedition, while at the same time affording to users

their right to a fair and public hearing. 5. Use of

accelerated proceedings should be encouraged, where appropriate. 6. In appropriate

cases, the appeal

options may be limited. In certain cases (e.g. small claims) the

appeal may be excluded, or a leave to appeal may be requested. Manifestly ill-founded appeals

may be declared inadmissible or rejected in a summary way. 7. The recourse to the highest instances should be limited to the cases that deserve their

attention and review. |

As for the

guidelines addressed to judges,

they are enshrined in part

V, as follows:

|

V. A. Active case management 1. The judge should have sufficient powers to manage the

proceedings actively. 2. Subject to general rules,

the judge should be authorised to set appropriate time limits and adjust time management to the

general and specific targets as well as to the particulars of each individual

case. 3. Standard electronic templates

for the drafting of judicial decisions and judicial decision support software

should be developed and used by judges and court staff. V. B. Timing agreement with

the parties and lawyers 1. In the time management of

the process, due consideration should be given to the interests of the users.

They have the right to be involved in the planning of the process at an early

stage. 2. Where possible, the judge

should attempt to reach agreement with all participants in the procedure

regarding the procedural calendar. For this purpose, he should also be

assisted by appropriate court personnel (clerks) and information technology. 3. The deviations from the

agreed calendar should be minimal and restricted to justified cases. In

principle, the extension of the set time limits should be possible only with

the agreement of all parties, or if the interests of justice so require. V. C. Co-operation and

monitoring of other actors (experts, witnesses

etc.) 1. All participants in the

process have the duty to co-operate with the court in the observance of set

targets and time limits. 2. In the process, the judge

has the right to monitor

the observance of time limits by all participants, in particular, but not

restricted to, those invited or engaged by the court, such as witnesses or

experts. V. D. Suppression of procedural

abuses 1. All attempts to willingly

and knowingly delay proceedings should be discouraged. 2. There should be

procedural sanctions for causing delay and vexatious behaviour. These sanctions can be applied

either to the parties or their representatives. 3. If a member of a legal profession grossly abuses

procedural rights or significantly delays the proceedings, it should be

reported to the respective professional organisation for such sanctions as

may be appropriate. V. E. The reasoning of judgments 1. The reasoning of all

judgments should be concise

in form and limited

to those issues

requiring to be addressed.

The purpose should be to explain the decision. Only questions relevant to the

decision of the case should be taken into account. 2. It should be possible for judges, in

appropriate cases, to

give an oral judgement with a written decision. |

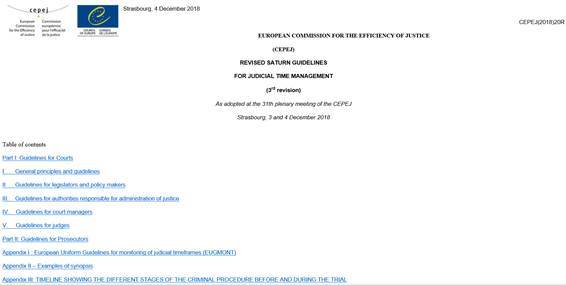

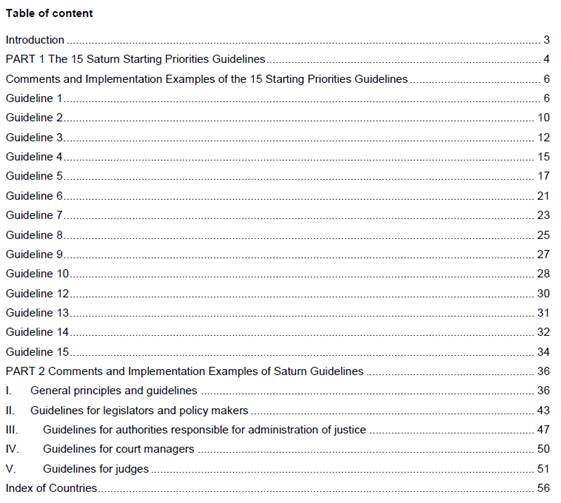

The above-mentioned Guidelines are complemented by a

gathering of comments and (good) examples of implementation of the document.

This text is called Comments and implementation

examples of the SATURN guidelines. The document is structured around

15 out of the whole

collection of guidelines, which is to say, the guidelines which have been

thought to be most

relevant.

|

|

|

|

|

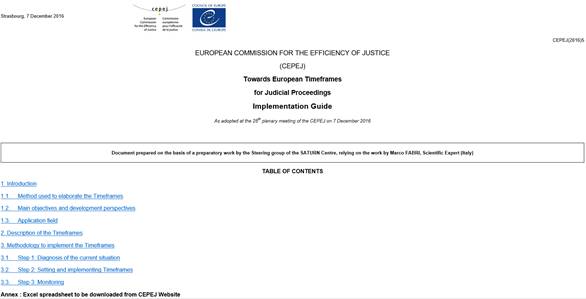

Another relevant tool

created and adopted by the CEPEJ SATURN Centre is the Implementation guide “Towards

European timeframes for judicial proceedings”.

|

|

The guide intends timeframes as one of the tools available for the

attainment of the goal

set in Article 6 of the European Convention

on Human Rights, according to which “everyone is entitled to a fair and public

hearing within a reasonable time”. Timeframes can be considered operational tools, because they are concrete

targets to measure to what extent each court, and more generally the

administration of justice, pursue the timeliness of case processing, and then

the principle of fair trial within a reasonable time stated by the European

Convention on Human Rights.

The setting of

Timeframes is a fundamental

step to start measuring and comparing case processing performance and defining conceptually

better the “Backlog”,

which is the number or

percentage of pending cases that do not accomplish the set or planned timeframe.

Timeframes should

be set not only for the three

major areas (civil,

criminal, administrative), but they

should progressively be set also

for the different “Case categories” dealt

with by the court. Timeframes should be tailored to each case category (e.g. family matters, bankruptcy,

labour etc.), and local circumstances, depending on procedural issues, resource

available, and legal environment. However, a European indication is a fundamental lighthouse to develop

Timeframes at the national and local levels, and to start building a shared

vision of common expectations across Europe.

The Timeframes

proposed in our guide are the result of a process

which was carried out in the following steps:

·

analysis of the literature on judicial timeframes;

·

b) case law of the European Courts of Human Rights;

·

c) data collection and analysis of two surveys

submitted to both National Correspondents and Pilot Courts of the CEPEJ;

·

d) discussion of the proposed Timeframes during the

2014, 2015, 2016 meetings of the CEPEJ Pilot Courts and the CEPEJ plenary

meeting in December 2015 and June 2016.

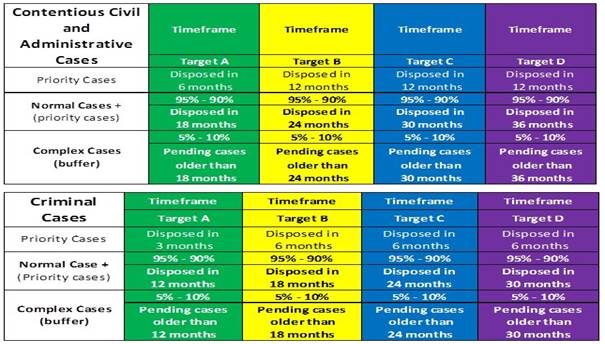

The result of this

process are the proposed four

sets of timeframes (A, B, C, D), which take

into consideration the large variety of situations in the member States.

|

|

Based on the data

available, we are aware that some countries will not be able to meet the

Timeframes proposed, while some others will probably be able to do even better.

These four Timeframes may be used as a basic reference. Each country or court is invited to establish its own Timeframes for each court

and case category. The same or different Timeframes should be applied also for each instance of the

whole judicial process (first, appeal, Supreme Court instance). For example,

Timeframe D can be realistic and set for first instance courts, at least as a

starting point, while Timeframe A can be used in Supreme Courts.

As for the

objectives, we believe that these Timeframes are a pragmatic compromise of very different situations

and contexts of the various member States. They should be seen as objectives to be progressively reached step by step by

all the member States, also in the light of the need to promote justice

services and a similar length of judicial proceedings quite similar across

Europe. This entails that

the overall objective for all the Council of Europe member States should be to

reach Timeframe A for all the proceedings, with a progressive approaching, for

example through Timeframe B and C.

We may add that in

the last year the CEPEJ SATURN Centre has made an effort in order to single out

some particular case categories, such as:

·

Intellectual Property,

·

Medical Malpractice and

·

Car Accidents Lawsuits.

The Centre activated

the Network of Pilot Courts of the CEPEJ through a questionnaire in order to

get data and information on compliance with the above-mentioned timeframes

according to the different categories of cases. Several European Pilot Courts

participated in the survey and the final results were discussed during the

meeting of the Pilot Courts Network held in Barcelona on 4th

October, 2019.

5. Other Tools and Main Studies on Judicial

Time Management.

Among the other tools

elaborated by the CEPEJ SATURN Centre we may mention the Guide

for implementing the SATURN management tools in courts.

|

|

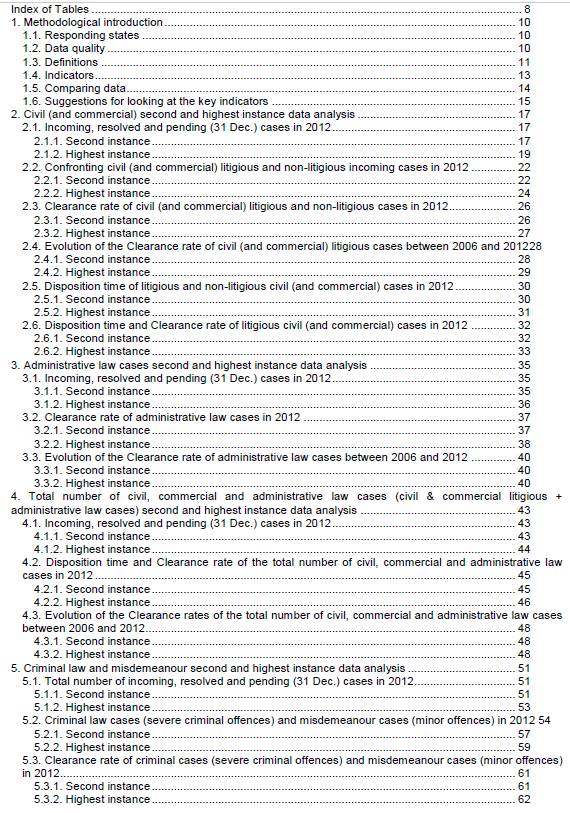

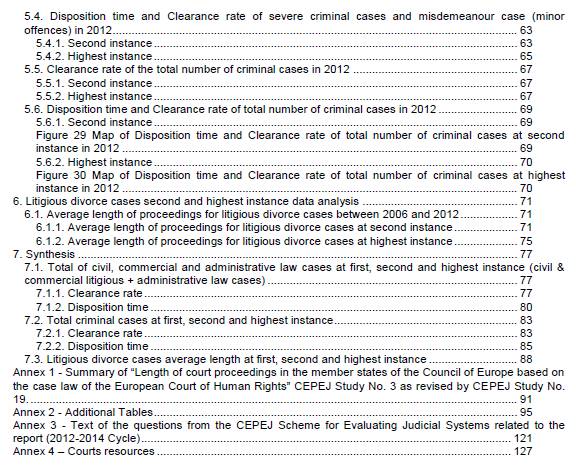

Among the most

relevant studies

that have already been done by impulse and under the control of the CEPEJ

SATURN Centre we may mention the following:

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. On-going Works within the

CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time Management. New Approaches and Tools on Case Management in Europe: Case Weighting.

The CEPEJ SATURN

Centre is currently studying an array of new tools and systems to deal with contemporary

challenges in the field of case management. These sectors represent the new challenges

of case management in Europe.

In this framework I

would like to mention in particular the issue of Case Weighting, whose main aim is that of allowing

allows a Court (or a Court system as a whole) to assess the complexity of the

cases they have to deal with. The Steering Group is therefore working (with the

help of two scientific experts) on a document, whose main features are:

·

Awareness of the fact that,

in a nutshell, two different kinds of approaches are possible:

o the approach on the time

implying a breakdown of the trial stages and

o the approach made of points

based on criteria of complexity of the case.

·

Experience acquired

through:

o a study visits to

Israel (thanks

to Israeli Supreme Court and to Israeli representative, Dr Gali Aviv), which studied and

implemented a remarkable time-based

method,

o discussions within the meeting of the Pilot Courts (in Barcelona on the 4th

October, 2019),

o an ad hoc meeting

planned for 2020 in Paris with representatives of the most relevant European national

experiences in this field.

·

Results acquired through a questionnaire spread

among CEPEJ national

correspondents

·

Work is going on with the help of two scientific experts: Prof. Marco Fabri (Italy) and Prof.

Shanee Benkin (Israel), on the basis of the following scheme:

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||

|

Time-based system |

Point-based system |

Mixed system |

|||

|

Measurement of working time (ex.: Israel) |

Estimation of working time (ex.: Germany, Austria) |

Total number of points

for various case-related factors such as: ·

number of files ·

number of pending cases ·

time required to examine a

case ·

number of parties ·

number of hearings ·

need of one or more expertises ·

number of pretensions in a case, ·

number of lawyers’ submissions in a case, ·

need to hear witnesses (and number of them), etc. |

Time + other case-related indicators |

||

·

Getting CCEJ somehow involved in

the project.

·

The CEPEJ-SATURN also considered and approved the draft table of contents and the draft list of

objectives of the future

tool as drawn up by the two experts.

|

|

|

7. On-going Works within the

CEPEJ SATURN Centre for Judicial Time Management. New Approaches and Tools on Case Management in Europe: Dashboards for Court Management.

In these last years and months, the

works of the CEPEJ SATURN Centre have been going on also on other important

aspects of judicial activity. We might here mention:

· the work about the elaboration of tools,

guidelines

(possibly a handbook)

and IT instruments

for the Management of judicial time regulations

for criminal cases, according

to EcvHR articles 5 and 6;

· a reflection about a document on the Role of the parties and the practitioners in preventing delays

in court proceedings (with the involvement of CCBE);

·

the development of

co-operation activities and Court-coaching programmes in Albania, Kosovo, Malta and Slovakia;

·

the elaboration of a contribution in the

updating of Recommendation Rec(86)12 concerning measures to prevent and reduce the excessive

workload in the courts;

·

the co-ordination of the

works of the Network of the Pilot courts of the CEPEJ.

·

(For an updating of the information concerning the

activities of CEPEJ-SATURN see: https://www.iaj-uim.org/iuw/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Oberto_Presentation_for_ECHR_oral.pdf).

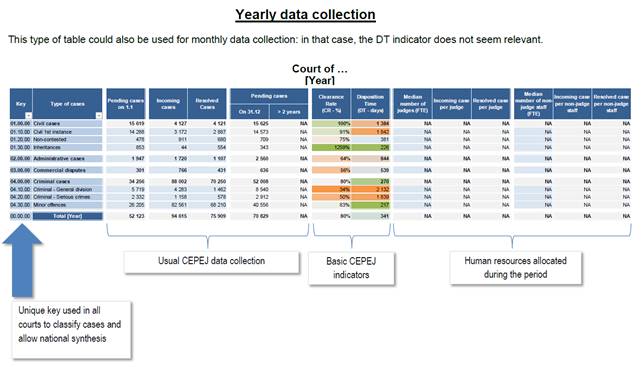

A special mention has to be made about the subject of Dashboards for court management. Here the CEPEJ SATURN Centre started its works on

the basis of a first draft document, which contained the following template

dashboard:

|

|

|

|

|

|

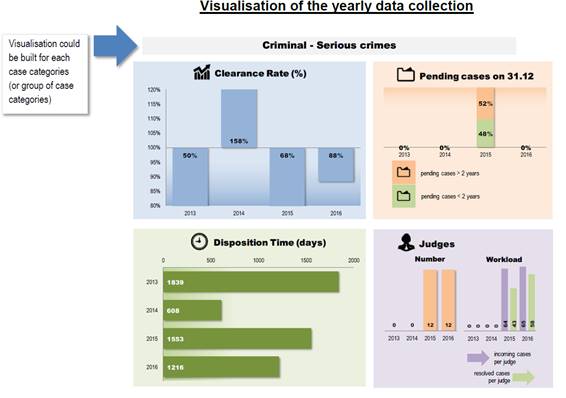

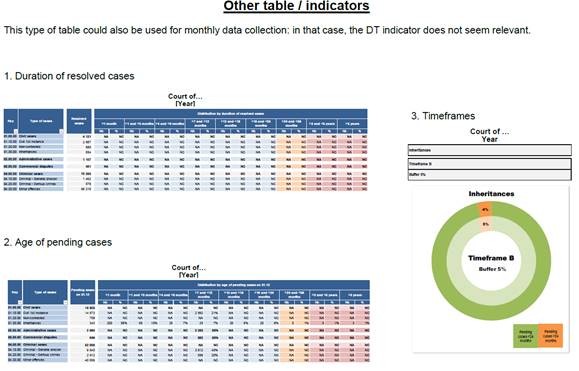

Actually, the CEPEJ SATURN Centre instructed the CEPEJ Secretariat to continue

collecting information on existing dashboards. On the basis of the analysis of

several European experiences the CEPEJ-SATURN’s work on court management

dashboards is to produce a common template that would be made available to all

European courts, containing guidelines on the data, tables, graphics and

indicators that could be included in a dashboard template (on the number of

cases per judge or the duration of cases, for example in the light of the

discussions held at the Pilot courts meeting), along with a number of examples.

According to the recipient of the dashboards, the shape and the content

of the table / graphics could evolve:

·

For court managers –

monthly and yearly indicators, to measure efficiency of the court and allocate

means could be relevant.

·

At national / federal

level, other economic and social indicators could be crossed with the

efficiency of the courts: e.g., evolution of demography, unemployment, etc.

·

To promote widely the

activity of the judiciary, specific graphics / tables could be built and

published on internet (see for example CEPEJ-STAT).

Additional

information (in English) on the current debate on issues of case management (in

Italy and Europe) is available here:

·

G. Oberto,

Study on Measures Adopted in Turin’s

Court (“Strasbourg Programme”) along the Lines of “Saturn Guidelines for

Judicial Time Management”, https://www.giacomooberto.com/study_on_Strasbourg_Programme.htm.

·

F. Contiki

(ed.), Handle with Care: assessing and

designing methods for evaluation and development of the quality of justice,

IRSIG-CNR. Bologna, 2017,

https://www.lut.fi/web/en/school-of-engineering-science/research/projects/handle-with-care.

·

E. Silvestri,

Notes on Case Management in Italy,

https://ssrn.com/abstract=3158105

or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3158105.

·

D. C. Steelman

& M. Fabri, Can an Italian Court Use the American Approach

to Delay Reduction?

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0098261X.2008.10767868.

·

L. Verzelloni,

Reduction of Backlog: The Experience of

the Strasbourg Programme and the Census of Italian Civil System,

·

G. Esposito,

S. Lanau, S. Pompe, Judicial System Reform in Italy—A Key to Growth,

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2014/wp1432.pdf

·

Imf, Italy, selected figures,