PRENUPTIAL

AGREEMENTS

IN

CONTEMPLATION OF DIVORCE:

EUROPEAN

AND ITALIAN PERSPECTIVES

“To leave poor me thou hast

the strength of laws,

Since why to love I can allege no cause.”

(Shakespeare, Sonnet 49)

|

Table of Contents: 1.

Prenuptial Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce: an Historical Overview. – 2. Prenuptial Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce in the

U.S.A. – 3. Prenuptial Agreements in Contemplation of

Divorce in the United Kingdom. – 4. Prenuptial

Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce in Continental Europe: Catalonia and

Germany. – 5. The Case of France. – 6.

Prenuptial Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce in Italy. |

1. Prenuptial Agreements

in Contemplation of Divorce: an Historical Overview.

A prenuptial

agreement, antenuptial agreement, or premarital agreement, commonly abbreviated

to prenup or prenupt, is a contract

entered into prior to marriage by the people intending to marry. The content of a prenuptial

agreement can vary widely, but commonly includes provisions for division of property and spousal support in the event of divorce or breakup of marriage. They

may also include terms for the forfeiture of assets as a result of divorce on

the grounds of adultery; further conditions of guardianship may be included as

well.

Postnuptial agreements are similar to prenuptial

agreements, except that they are entered into after a couple is married.

Coming to the history of prenups, I have

to point out that the widespread idea, according to which they would be

something “new,” something foreign to our legal tradition, is not entirely

true. Let me cite some examples.

Many rules of the Roman Law referred to the

agreements between prospective spouses (or their families), called pacta nuptialia (marriage agreements), very often called as

well “pacta antenuptialia,” or “pacta ante nuptias,” with a terminology which

is very similar to some current expressions, still in use nowadays, such as “antenuptial

agreements.” One of the most recurring elements in such contracts was the right

of spouses to provide for the restitution of the dowry. Dowry was the transfer of money and/or

of other kinds of assets (movable, real estate, etc.) from the bride (or, more

often, her family) to the groom, at the moment of the marriage, in order to contribute a share of the

costs involved in setting up a new household (ad onera matrimonii ferenda). The husband had the right to manage

those assets, to perceive their fruits and interests (in order to use them for

the family’s sake), but he was not their legal owner, at least in the full meaning of the word,

as, the moment of the dissolution

of marriage, he (or his heirs) had to give back the dowry.

Pacta nuptialia could therefore include agreements

concerning, among other things, the person to whom the dowry had to be given back (either the wife, or

her family: father, brothers, heirs, etc.). Grounds of dissolution of marriage

in Roman Law were not only death or capitis

deminutio maxima (e.g. if the spouse was taken as a prisoner of war and was

sold as a slave), but also divorce. Therefore roman sources inform us extensively on this matter and we may find

there many rules on

how, to whom, in what time, etc. the

dowry should have been given back in case of divorce. Moreover, many laws of

the Digest and of the Codex of

Justinian show that the envisaged scenario “par

excellence” of dissolution of marriage was divorce, as the event that in most cases

parties had in mind while concluding an agreement on patrimonial consequences

of their future marriage.

|

“Cum quaerebatur, an verbum: Soluto matrimonio

dotem reddi, non tantum

divortium, sed et

mortem contineret, hoc est, an de hoc quoque casu contrahentes

sentiant? Et multi putabant hoc sensisse; et quibusdam aliis contra

videbatur: secundum hoc motus Imperator pronunciavit, id actum eo pacto, ut nullo casu remaneret dos apud maritum.”

(D. 50, 16, 240). |

“It was asked, whether the expression

‘dowry to be given back in case of dissolution

of marriage’ should encompass not only divorce, but also the case of

death: which is to say, whether parties to such an agreement would intend

that this contract refers also to this latter case [i.e. to death and not only to divorce]. Many (jurists) thought

this was the case, but some others had a different mind. The Emperor decided

that in no case dowry should stay with the husband.” (D. 50, 16, 240). |

Also in the following centuries we

find evidences of prenuptial agreements aimed at setting patrimonial rules on

the assets of the parties in case of marriage crisis (legal separation, in this

case, as, of course, divorce was not allowed by the Catholic Church). The first

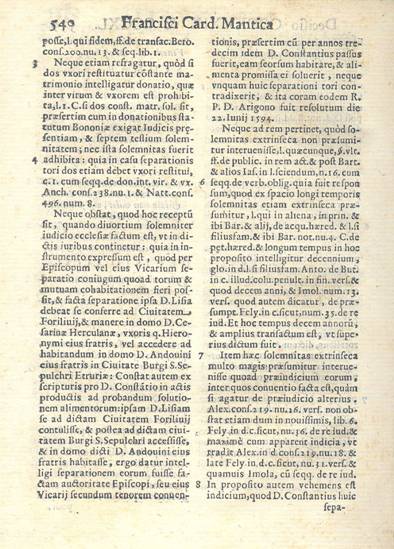

case I would like to mention deals with a decision issued at the end of the 16th century

by the Rota Romana on the validity of a marriage

contract that we could surely describe, in modern terms, as a prenuptial

agreement in contemplation of the marriage crisis.

|

«Placuit Dominis, sententiam

esse confirmanda: quia cum convenerit, ut in eventum separationis tori, D. Constantius

teneretur D. Lisiae eius uxori praestare scuta 270, pro alimentis, et si in

solutione eorum cessaverit per annum, ipsa possit agere ad restitutionem

totius dotis: & D. Constantius dictam summam non solverit anno 1589.

necessario sequitur, quod dos eidem D. Lisiae debeat restitui». |

«The Judges [of the Rota Romana] decided to uphold the

[first instance] judgement: as it had been agreed upon that, in case of legal

separation, (a) Mr. Constantine would be obliged to pay to Mrs. Lisia, his

wife, [every year] 270 scuta [silver

currency unity of the time, in the Papal States, the current

value of one scutum being of

about € 75,00], as alimony, and (b) should Mr. Constantine stop to pay the

said amount for one year, she could sue him and ask the Court to oblige him

to give back all the dowry; [it happened that] Mr. Constantine did not pay that amount for

the year 1589; therefore it was decided that he had to give back the dowry to

Mrs. Lisia» (Bononien. restitutionis dotis, 16 May 1595, in Mantica,

Decisiones Rotae Romanae, Romae, 1618, p. 539). |

|

|

|

In this case the Rota Romana

(second instance and supreme court in the Papal States) decided to uphold the

first instance court decision, taken by the Rota

of Bologna, that had declared valid and enforceable the agreement concluded before the marriage by a

couple of that city. According to such premarital contract, the husband had

promised to pay every year a certain amount of money in case of legal separation.

He also had promised that, should he breach that obligation for one year, his

wife could sue him and ask for restitution of the whole of her dowry. As he

failed to pay alimony for the year 1589, he was sentenced to give back the

dowry.

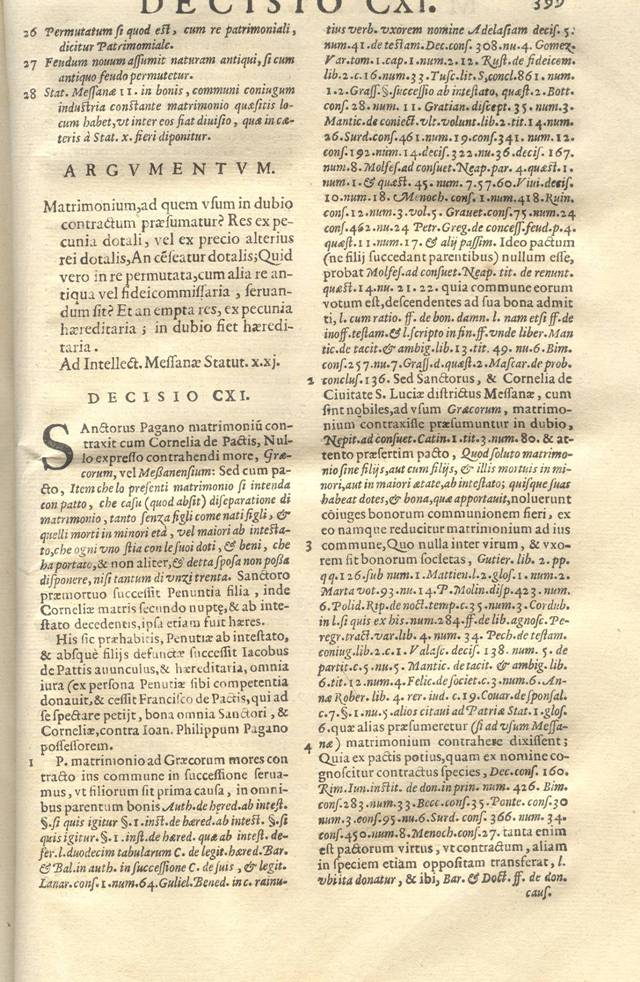

Even more interesting is the following case, decided on 20 June 1612 by the Supreme Court of Sicily.

|

«Sanctorus

Pagano matrimonium contraxit cum Cornelia de Pactis, Nullo expresso

contrahendi more, Graecorum, vel Messanensium: Sed cum pacto, Item che lo presenti matrimonio si intenda

con patto, che casu

(quod absit) di separatione

di matrimonio, tanto senza figli come nati figli, et quelli morti in minori età, vel

maiori ab intestato, che ogni

uno stia con le suoi doti, et beni, che ha portato, et non aliter, et detta sposa non possa disponere, nisi

tantum di unzi trenta». |

«Mr. Santoro Pagano married

Mrs. Cornelia de Pactis, without making any kind of express choice for the

“Greek” or “Messina” marriage [i.e. the system of separation of assets, with

the consequence that the marriage had to be considered as ruled by the

“Latin” system of universal community of assets], But with the following

clause: That this marriage should be intended that, in case (God forbid) of

legal separation of marriage, without children, or, should children be born,

should they die while minors, or, if come of age, die without having made

last will and testament, anyone [husband, wife and children] will keep

his/her dowries and assets he/she brought in the marriage, and nothing more,

and the said bride will have only the amount of thirty unzi [unzo, onza, or oncia was the golden currency unit of

the Kingdom of Sicily at those times, its current

value being of about € 180,00]». (See

Giurba,

Decisionum novissimarum Consistorii

Sacrae Regiae Conscientiae Regni Siciliae, I, Panormi, 1621, p. 399). |

|

|

In a curious mixture of Italian and Latin, the

Sicilian notary had provided for that, in case of separation, the customary community of goods (this

form of general co-ownership of goods being the regular default system of asset regulations

between husband and wife in the Sicilian city of Messina at those times) would

be considered as if it had never been existing for that couple.

This is not the

only example of an agreement of this kind in Europe. The French tradition knows

very well the so called “Clause

Alsacienne” (Alsatian Clause), according to which a couple can choose

the system of general

community of assets (comprising also real estates and goods acquired by

each of the spouses before the marriage), but, in case of divorce, the dissolution of marriage

will operate as a resolutory

condition.

The final result is that if

the couple does not part

and marriage comes to an end by

death, the rules of

co-ownership shall apply and the surviving spouse will keep his/her share (and of course will

add the share coming from the heritage); if, on the contrary, the marriage is a “failure,” the system of community (that logically

presupposes a couple in which husband and wife are not at odds…) will be “annulled,” as if the two of them had never

been married: what makes of course a lot of sense! (For further information on the “Alsatian Clause” see Oberto, La comunione legale tra coniugi, in Trattato di diritto civile e commerciale Cicu-Messineo, I, Milano,

2010, p. 386, note 171; II, Milano, 2010, p. 1671, footnote 198; Id., Suggerimenti

per un intervento in tema di accordi preventivi sulla crisi coniugale,

in Famiglia e diritto, 2014, p. 90,

footnote 11).

2. Prenuptial Agreements

in Contemplation of Divorce in the U.S.A.

Coming to the present state of the

situation, we know that such agreements are widely known and practised in the United States.

Historically, judges in the United States accepted the view

that prenuptial agreements were corrupting what marriage was supposed to stand for, and often they would not recognize them.

Actually, it was not until

1976 that two Supreme Courts (California, in

Re Marriage of Dawley and Connecticut, Parniawski

v Parniawski) decided to uphold and enforce two prenups. Actually this happened only

after states legislations got rid of the ancient rule of divorce based on the

fault of one of the spouses. Before such reforms, which occurred in the

mid-Seventies of the 20th Century, premarital agreements in

contemplation of divorce were seen as way for the husband “to buy himself out the marriage,

regardless of the circumstances of the divorce” (see the Supreme Court

of Maryland in the 1956 case Cohn v Cohn:

further information in Oberto, I contratti della crisi coniugale,

Milano, 1999, p. 494 ff.).

Currently prenups are recognized, although they may not always be enforced.

Both parties should have lawyers represent them to ensure that the agreement is

enforceable. Some attorneys

recommend videotaping the signing, although this is optional. Some

states such as California require that the parties be represented by counsel if spousal

support (alimony) is limited or waived.

Prenuptial

agreements are, at best, a partial solution to obviating some of the risks of

marital property disputes in times of divorce. They protect minimal assets and

are not the final word. Nevertheless, they can be very powerful and limit parties’ property rights and alimony. It may be impossible to set aside

a properly drafted and executed prenup. A prenup can dictate not only what

happens if the parties divorce, but also what happens when they die, as Common Law

systems do not know the Civil Law principle which forbids agreements on future heritage of

a living person. Therefore, American prenups can act as contracts to make a will and/or eliminate all your rights to property, probate

homestead, probate allowance, right to take as a predetermined heir, and the

right to act as an executor and administrator of your spouse’s estate.

In the United

States, prenuptial agreements are recognized in all fifty states and the District of Columbia.

Likewise, in most jurisdictions, some elements are required for a valid prenuptial

agreement:

1.

agreement must be in writing (oral prenups are generally

unenforceable);

2.

full and/or fair disclosure at the time of execution;

3.

the agreement cannot be unconscionable.

With respect to financial issues

ancillary to divorce, prenuptial agreements are routinely upheld and enforced

by courts in virtually all states. There are circumstances in which courts have

refused to enforce certain portions/provisions of such agreements. For example,

in an April, 2007 decision by the Appellate Division in New Jersey, the court

refused to enforce a provision of a prenuptial agreement relating to the wife’s

waiver of her interest in the husband’s savings plan. The New Jersey court held

that when the parties executed their prenuptial agreement, it was not

foreseeable that the husband would later increase his contributions toward the

savings plan.

In California parties can waive disclosure beyond that

which is provided, and there is no requirement of notarization, but it is good practice. There are special

requirements if parties sign the agreement without attorney, and the parties

must have independent

counsel if they limit spousal support

(also known as alimony or spousal maintenance in other states). Parties must wait seven days after the premarital

agreement is first presented for review before they sign it, but there is no requirement

that this be done a certain number of days prior to the marriage. Prenups often

take months to negotiate so they should not be left until the last minute (as

people often do). If the prenup calls for the payment of a lump sum at the time

of divorce, it may be deemed to promote divorce. This concept has come under

attack recently and a lawyer should be consulted to make sure the prenup does

not violate this provision.

In California, Registered Domestic Partners

may also enter into a prenup. Prenups for Domestic Partners can have added

complexities because the federal tax treatment of Domestic Partners differs

from that of married couples.

A sunset provision may be

inserted into a prenuptial agreement, specifying that after a certain amount of

time, the agreement will

expire. In a few states, such as Maine, the agreement will automatically

lapse after the birth of a child, unless the parties renew the agreement. In

other states, a certain number of years of marriage will cause a prenuptial

agreement to lapse. In states that have adopted the UPAA

(Uniform Premarital Agreement Act), no sunset provision is provided by

statute, but one could be privately contracted for. Note that states have different

versions of the UPAA.

In drafting an

agreement, it is important to recognize that there are two types of state laws that govern divorce – equitable distribution,

of which there are 41

states and 9 states

that are some variation of community

property. An agreement written in a community property state may not be

designed to govern what occurs in an equitable distribution state and vice

versa. It may be necessary to retain attorneys in both states to cover the

possible eventuality that the parties may live in a state other than the state

they were married. Often people have more than one home in different states or

they move a lot because of their work so it is important to take that into

account in the drafting process.

3. Prenuptial

Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce in the United Kingdom.

Prenuptial

agreements have historically not

been considered legally valid

in Britain. This

was true until the test case between the German heiress Katrin

Radmacher and Nicolas Granatino, indicated that such agreements can

“in the right case” have decisive weight in a divorce settlement. The judgments of the Appeal Court

and of the Supreme Court of Britain in Radmacher

v Granatino stand as a landmark

in the history of English matrimonial and divorce law. They clearly established

that, contrary to the previous line of authority holding that pre-nuptial

agreements were against public policy, they were now to be given effect to so

long as they were entered into by both parties freely and with full

appreciation of their consequences.

The parties were

both foreign nationals, the wife

German (whose

assets are assessed at about £ 100,000,000) and the husband French, who had signed a pre-nuptial agreement valid under German law

but then divorced

in the UK. In the High Court Baron J had awarded the husband £ 5.6m even though the

pre-nuptial agreement had stated

that neither party would seek maintenance from the

other in the event of divorce. The wife therefore appealed.

Giving the lead

judgment Thorpe LJ

allowed the wife’s appeal broadly on the grounds that Baron J had not given

sufficient weight to the existence of agreement in her initial award, though

still providing the husband with some housing and other funds to reflect the

shared residence of the couple’s children. At paragraph 53 of the judgment he

also made the following statement “in future cases broadly in line with the present case on the facts, the

judge should give due weight to the marital property regime into which the

parties freely entered. This is not to apply foreign law, nor is it to give

effect to a contract foreign to English tradition. It is, in my judgment, a

legitimate exercise of the very wide discretion that is conferred on the judges

to achieve fairness between the parties to the ancillary relief proceedings.”

Other relevant

parts of the reasoning by Lord Justice Thorpe:

“There are many

instances in which mature couples, perhaps each contemplating a second

marriage, wish to regulate the future enjoyment of their assets and perhaps to

protect the interests of the children of the earlier marriages upon dissolution

of a second marriage. They may not unreasonably

seek that clarity before making the commitment to a second marriage. Due respect for adult autonomy suggests that, subject of course

to proper safeguards, a carefully

fashioned contract should be available as an alternative to the stress, anxieties and expense of a submission to the width of the

judicial discretion.”

“I also hold my

opinion because: i) In so far as the rule that such contracts are void survives, it seems to me

to be increasingly

unrealistic. It reflects the laws and morals

of earlier generations. It does not sufficiently

recognise the rights of autonomous adults to govern their future financial

relationship by agreement in an age when marriage is not generally regarded as

a sacrament and divorce is a statistical commonplace.”

“As a society we

should be seeking to reduce and not to maintain rules of law that divide us

from the majority of the member states of Europe. Europe apart, we are in

danger of isolation in the wider common law world if we do not give greater

force and effect to ante-nuptial contracts.”

“In the

circumstances, I agree in effect with my Lords that this is a case in which the

pre-nuptial agreement

made by the parties should be given decisive weight in the section 25 exercise.

Their agreement was

entered into willingly and knowingly by responsible adults. The

husband had a proper understanding of the consequences of his agreement. It is

to be inferred that without that agreement no marriage would have taken place,

and that the wife’s father would not have made over to her the additional

resources which followed her marriage. The parties entered into their agreement with the help and

advice of a German lawyer, under German law, making an agreement which was

familiar to the civil law under which both parties and their families had grown

up in Germany and France.”

The decision by the

Court of Appeals has been confirmed by the Supreme Court, in the year 2010.

Relevant parts of

the S.C. reasoning:

“We would advance

the following proposition, to be applied in the case of both ante- and

post-nuptial agreements, in preference to that suggested by the Board in

MacLeod: ‘The court should

give effect to a nuptial agreement that is freely entered into by each party

with a full appreciation of its implications unless in the circumstances

prevailing it would not be fair to hold the parties to their agreement.’”

“91. On 1 August, 1998 the parties attended at the office of Dr Magis near

Düsseldorf. Their meeting with him lasted for between two and three hours. The

husband told Dr Magis that he had seen the draft agreement but that he did not

have a translation of it. Dr Magis was angry when he learned of the absence of

a translation, which he considered to be important for the purpose of ensuring

that the husband had had a proper opportunity to consider its terms. Dr Magis

indicated that he was minded to postpone its execution but, when told that the

parties were unlikely again to be in Germany prior to the marriage, he was

persuaded to continue. Dr

Magis, speaking English, then took the parties through the terms of the

agreement in detail and explained them clearly; but he did not offer a

verbatim translation of every line. The parties executed the agreement (which

bears the date of 4 August, 1998) in his presence.”

“The agreement

stated (in recital 2) that (a) the husband was a French citizen and, according to his own

statement, did not have a

good command of German, although he did, according to his own statement and in the opinion of

the officiating notary (Dr Magis), have an adequate command of English; (b) the

document was therefore read out by the notary in German and then translated by

him into English; (c) the parties to the agreement declared that they wished to

waive the use of an interpreter or a second notary as well as a written

translation; and (d) a draft of the text of the agreement had been submitted to

the parties two weeks before the execution of the document.”

“Clause 1 stated

the intention of the parties to get married in London and to establish their

first matrimonial residence there. By clause 2 the parties agreed that the

effects of their marriage in general, as well as in terms of matrimonial

property and the law of succession, would be governed by German law. Clause 3

provided for separation of property, and the parties stated: "Despite

advice from the notary, we waive the possibility of having a schedule of our

respective current assets appended to this deed.”

Clause 5 provided for

the mutual waiver of claims for maintenance of any kind whatsoever following

divorce:

“The waiver shall apply to the

fullest extent permitted by law even should one of us – whether or not for

reasons attributable to fault on that person’s part – be in serious

difficulties.

The notary has given us detailed advice about the

right to maintenance between divorced spouses and the consequences of the

reciprocal waiver agreed above.

Each of us is aware that there may be significant

adverse consequences as a result of the above waiver.”

The Supreme Court further dismisses the argument of the First

Instance Judge, according to which parties had not received independent legal advice,

remarking that the Notary

had provided sufficient information on

the consequences of that agreement.

“114. The Court of Appeal differed from the finding of the

trial judge that the ante-nuptial agreement was tainted by the circumstances in

which it was made. Wilson LJ, with whom the other two members of the court

agree, dealt with these matters in detail. The judge had found that the husband had lacked independent legal

advice. Wilson LJ

held that he had well

understood the effect of the agreement, had had the opportunity to take

independent advice, but had failed to do so. In these circumstances he could

not pray in aid the fact that he had not taken independent legal advice.

115. The judge held that the wife had failed to disclose the

approximate value of her assets. Wilson LJ observed that the husband knew that the wife had

substantial wealth and had shown no interest in ascertaining its approximate

extent. More significantly, he had made no suggestion that this would

have had any effect on his readiness to enter into the agreement.

116. The judge held that the absence of negotiations

was a third vitiating factor. Wilson LJ observed that the judge had given no explanation

as to why this was a vitiating factor, and that the absence of

negotiations merely reflected the fact that the background of the parties

rendered the entry into such an agreement commonplace.

117. We agree with the Court of

Appeal that the judge was wrong to find that the ante-nuptial agreement

had been tainted in these ways. We also agree that it is not apparent that the

judge made any significant reduction in her award to reflect the fact of the

agreement. In these circumstances, the Court of Appeal was entitled to replace

her award with its own assessment, and the issue for this court is whether the

Court of Appeal erred in principle.”

As a conclusion on

this case, we can further read in the reasoning of the judgment that “Our conclusion is that in the

circumstances of this case it is fair that he should be held to that agreement and that it would be

unfair to depart from it.

We detect no error of principle on the

part of the Court of Appeal. For these reasons we would dismiss this appeal.”

After this

benchmark case, the Law Commission, a

statutory independent body

that advises on law reform, recommended that prenups should become legally

binding subject to stringent

qualifications. One requirement should be that at the time of signing

both parties must disclose material information about their financial situation

and have received legal advice. A further restriction, under the commission’s

proposals, is that agreements would only be enforceable “after both partner’s

financial needs, and any financial responsibilities towards children, have been

met.” Introducing prenuptial agreements without protection of the

parties’ needs

“would be very damaging,”

the commission warns. That key proviso suggests tortuous legal disputes over

the fairness of

maintenance payments and financial needs would still have to be brought before courts.

The Commission has

also called on the Family

Justice Council, whose members include judges and lawyers, to produce “authoritative guidance on

financial needs” to enable couples to reach an agreement that recognises their financial

responsibilities to each other. The Government, the Commission said, should also fund a “long-term study to assess whether a workable, non-statutory formula could be produced that

would give couples a clearer

idea of the amounts that might need to be paid to meet needs.”

The Law

Commission’s proposals will

be sent to the Ministry of Justice, which will examine whether it wishes

to draw up legislation on the basis of the suggestions. Past governments have

shown reluctance to revise marriage laws.

Legal doctrine has welcomed such recommendations, underlying

that qualifying nuptial agreements would give couples autonomy and control, and

make the financial outcome of separation more predictable. It has been remarked

furthermore that these recommendations represent a welcome stride towards

greater autonomy and certainty for couples. If implemented, then a prenup

fulfilling certain conditions will be legally binding. However, it has been remarked that it will

not be possible to avoid meeting the financial needs of partners and children

and, as always, the question is what falls under the definition of ‘needs’? In any case scholars

and practitioners agree on the positive effect of limiting judges’ discretion and of allowing couples greater

certainty and pre-agreed financial control should their relationship

disintegrate.

In the meantime, British Courts seem to follow the precedent of Radmacher v Granatino, as it is shown,

for instance, by a judgment of 2014 (SA v PA), in

which the (Dutch) husband contended that

the parties were bound by a Dutch

pre-marital

agreement and the (British) wife argued for a compensatory payment by virtue of

her having given up a high powered career. The Court upheld the agreement (signed in The

Netherlands by both parties before a Dutch notary) which contained provisions

on spousal assets, with exclusion of the immediate community (i.e. joint ownership) of all

property on marriage, which is the default marriage regime of Dutch law. On the

contrary, the contract

provided for the equal

sharing of the marital

acquest inasmuch as it provided for the joint sharing of surplus joint

income. The contract did

not provide for what maintenance,

if any, should be paid on divorce, in contrast to the German agreement in Granatino.

In any case the rationale of this

decision is clearly

the same of that

precedent, as the “core”

of it contains the following sentence: “The court should give effect to a nuptial agreement that

is freely entered into by each party with a full appreciation of its

implications unless in the circumstances prevailing it would not be fair to

hold the parties to their agreement.”

4. Prenuptial

Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce in Continental Europe: Catalonia and

Germany.

We saw that at the

basis of the rationale of Radmacher v Granatino lays the

assumption that, had such a prenup been brought before a court in France or in

Germany, it would have been considered as valid and enforceable. This remark is certainly true if we consider what

we call in Continental Europe the choice of the régime,

with particular reference to the choice for a system of separation of assets.

The situation is different if we have

regard to the antenuptial regulation of alimony (maintenance) in case of divorce or

separation. This possibility is

excluded in countries such as France or Italy,

whereas more and more countries in Continental Europe allow such provisions.

I could cite here

the case of the Family Law

Code of Catalonia

(Codi de familia), whose article 15

provided in 1998 the possibility for spouses to agree on assets and patrimonial

issues “àdhuc en previsió d’una ruptura matrimonial” (as well in contemplation

of a marriage crisis). This provision has been replaced in 2010 (see Llei 25/2010, del 29 de juliol, del llibre

segon del Codi civil de Catalunya, relatiu a la persona i la família) by article

231-20 of the Codi Civil de Catalunya,

which now dictates some interesting rules on the way such agreements have to be

made and enforced. Here it is as well interesting to remark that same

provisions are available to cohabiting

partners, according to article

234-5 of the same code.

As for Germany, one should

take into account that the contract autonomy of parties has always played a key

role, what reflects the thoughts of the greatest German philosophers. I could

her quote for instance Hegel (see Grundlinien

der Philosophie des Rechts, Leipzig, 1930, p. 147), who said that marriage

contracts (Ehepakten) were intended

to regulate relations between spouses “in case of separation of marriage for

death, divorce or similar events” (gegen

den Fall der Trennung der Ehe durch natürlichen Tod, Scheidung u. dergl.).

When considering

the German legal system we must always keep in mind two main factors.

(i) Since the early

16th century, Germany has known the insurgence of the Protestant doctrine,

which denied that

marriage could be considered as a sacrament: it was therefore much easier for German jurists of

the 16th, 17th and 18th century (such as

Thomasius, Struvius, Leyser, Lauterbach, Boehmer, etc.) to elaborate a new

doctrine of marriage. According to this new viewpoint, marriage could be seen just as a contract,

which, as any other contract, could be dissolved by mutual consent, with any kind of agreement on such dissolution.

(ii) Furthermore,

we must not forget that in many regions of Germany, Roman Law has been applied until 31st December,

1899; in the Roman legal system, as I have already pointed out, it was

accepted that spouses could provide for patrimonial consequences of a possible

divorce since the very moment in which they got married.

As a consequence,

German case law and German legal doctrine have always stated that such

agreements should be seen as valid

and enforceable, also when they foresaw a complete waiver of rights by

spouses in case of divorce.

So e.g., according

to a decision of the BGH (Supreme Court of

Germany) from 1995 “for agreements of financial kind, which spouses

precautionally already make during the marriage or even before the marriage

ceremony in contemplation of the case of a later divorce, exists the principle full freedom of contract

(§ 1408 Para. 1 and Para. 2 of the BGB-German

Civil Code). No special

control on the contents of such agreements has to take place, on whether

the regulation is appropriate. The enforceability of the agreement does not

depend on additional conditions, e.g. of the fact that for a maintenance

renouncement or waiver of spousal support a return or a payment of a

compensation is agreed upon” (see BGH 27.9.1995).

No effect on the enforceability

of the agreement was also played by the fact that “in such a case the

resolution to divorce could

turn out to be for economic reasons far more difficult to one spouse than the

other” (BGH 19.12.1989, FamRZ 1990, 372; see also BGH 2.10.1996).

According to this case law, German notaries have been developing different models of marriage contracts, which I describe in

my book about the “Contracts of Marriage Crisis” (I contratti della crisi coniugale). They may contain

clauses in which

one party (or both) waive any right to

alimony, such as: “the husband [or the wife, or both of them] gives up to

any pretension concerning alimonies in case of divorce, also in a situation of

need.” Among the many other

different possibilities we may find agreements in which alimony or divorce support are

not waived, but are determined

in a precise way, for instance by setting a limit (no more than € … for each month),

or by fixing the amount

of alimony as a ratio of the income of the “richest” party (e.g.: 20% of

the net income of the party who will have the highest income), or by setting a time limit (sunset provision) for

such alimonies (e.g.: for no longer than 5 years after dissolution of the

marriage). German marriage contracts (Eheverträge)

can also contain provisions in

case of death

of one of the spouses.

Some changes

were brought about by a decision

of the Federal Constitutional

Court in 2001

(BVerfG 6.2.2001), followed by a decision of

the Federal Court of

Justice (BGH 11.2.2004).

These two judgments ruled

that notarized prenuptial agreements that seriously disadvantage one party in a marriage could

be deemed invalid.

The judges stated that while, in principle, a contract may state that one of

the partners has renounced his or her right to receive alimony, if the agreement is one-sided

it would be morally unacceptable and could therefore be challenged. The court

also ruled that a spouse is free to contest the contract in instances of

imbalance where her partner’s income has risen dramatically during the marriage

because, for example, she was home caring for children.

Many scholars

have criticised

this view,

according to which the traditional freedom of parties in a contract is “patronized” by judges’

personal views. Moreover, powers of judges in Civil Law legal system do not

allow such kind of intervention on the “fairness” of an agreement, if parties

do not breach certain rules of the civil code: rules that however do not provide parties

(who freely and knowingly concluded an agreement) with the right to get rid of their

contractual engagements, simply because they changed their minds.

5. The Case of

France.

Also in France, as in any other country of Continental Europe, spouses

have the possibility to sign a marriage contract prior or during the marriage.

A French marriage contract (contrat de mariage)

deals (as in Italy, Spain, Germany etc.) with the possible consequences of the

marriage on the spouses properties acquired before or during the marriage. This

is the reason why in French law, as in Italy, Spain or Portugal, we use the

expression “matrimonial

regime,” the word “regime” meaning “rule” in languages of Latin origin

(in Latin language “regimen” means “governance,” or “management,” or

“administration”). A matrimonial regime is a body of rules about the effect of the marriage on the administration, the

enjoyment, the disposal of their property by the spouses during the marriage.

In French (as in Italian, Spanish, Portuguese etc.) law, the scope of a

marriage contract is to determine the matrimonial regime chosen by the spouses,

without any reference to

spousal support (maintenance or alimony) in case of legal separation or

divorce. So, marital agreements are legally valid and binding, but concern the

arm’s length division of assets and enrichment, without setting any “equitable

element” to try and pre-empt the divorce court right to “tip the scale”, whilst

in England (as well as in Common Law countries), they are essentially linked to

divorce and avoiding equitable distribution. According to many scholars, under

French law, one cannot exclude the right to a “compensatory payment” on the

occasion of divorce, contrary to German law, where it can be waived (as in Radmacher v Granatino).

However, I have to point out that—others than in Italy—French notaries, while

drafting a marriage contract, have a large power to “tailor” the property regime chosen by the spouses on their

needs, wishes and expectations. So, just to make an example, French courts deem

the already mentioned “Alsace

Clause” perfectly valid and enforceable; parties can furthermore provide

a community of acquests

regime in which the shares

of the spouses are not

equal, or where the rights of one of the parties can be paid off with a lump sum,

or with the conveyance of movable assets or of real estates, and so on (see on

this Oberto, La comunione legale tra coniugi, I, cit., p. 385 ff.; for some references

available online see as well Oberto,

Contratti prematrimoniali e accordi

preventivi sulla crisi coniugale, in

Famiglia e diritto, 2012, p. 69-103,

spec. §

3, footnotes 42-47).

Furthermore, some decisions issued in

cases concerning international

couples are showing that French judges are not against foreign

prenuptial agreements, as it is shown, for instance, by a 2010 judgement of the

Court

of Grasse. Here the judge upheld an English prenup, in which the parties

had agreed upon the fact that, in case of breakdown of the marriage, each

spouse would keep his or her assets, she would get £ 50,000.00 (indexed) for

each year of marriage (until the filing of a divorce petition) and this amount

was to cover any financial claim or remedy of any sort. At the time of

marriage, he also bought her a flat in her name on the Cote d’Azur, then worth

about £ 300,000.00

6. Prenuptial

Agreements in Contemplation of Divorce in Italy.

In Italy

marriage contracts can been concluded either before or during the marriage by

notary deed (see article 162 of the Italian Civil Code).

However—as I have

already explained—such deeds are mainly intended as instruments to chose a “marriage regime”

other than the default one, which is the

comunione legale (community

of acquests). However, the optional system of separazione dei

beni (separation of

assets) can be chosen

at the very moment of the celebration of marriage with a declaration of the

spouses to the mayor or to the parish priest celebrating the marriage.

By notary deed

spouses can also elect a fondo patrimoniale (capital fund, somehow

similar to a trust, by which spouses can chose to submit some assets—real

estates or negotiable instruments, such as securities, bonds, company shares,

etc.—to special rules, in order to allocate their revenues to the family

needs), but parties’ freedom

of movement in shaping the default community of acquests regime is very narrow, as no variation may be made in

the power to manage

and administer the assets belonging to the comunione

and parties cannot depart from the rule that the partition of the community

must be made in equal

portions. As an alternative

to comunione and separazione regimes spouses can chose a system of general community,

extended to (almost) all assets belonging to them and acquired either before or

after the celebration of the marriage (comunione

convenzionale).

However, as already

explained, the Italian Civil

Code does not

mention the matter of spousal

support among the subjects that a marriage contract can deal with.

Furthermore, the Supreme

Court of Cassation has always deemed null and void any agreement made in contemplation of a future divorce,

either concluded during the time of legal separation, or before.

In order to better

understand the position of the Court, one has to keep in mind that Italy is one of the last countries in the world

to allow divorce only to those couples who

have previously undergone

a judicial proceeding of legal separation. Currently, moreover, three years have to

elapse after the judicial proceeding of legal separation has been initiated,

before starting the procedure for divorce, even though a government bill,

currently discussed by the Parliament, could reduce such timeframe to one year.

Having said this,

it is easily understandable that very often couples

who reached an agreement

in the process of legal

separation would like to avoid any future possible dispute

during the divorce process. However, most agreements of that kind have been declared null and void by

the Supreme Court

of Cassation, at least in

the part in which they set forth provisions to be applicable in case of divorce (e.g.: the wife

gives up to any right to alimony and pledges not to claim alimony or lump sums

during the future divorce process). The reason is that such provisions could impair the freedom of both parties to decide whether to divorce or

not. Such influence

by possible pecuniary

consequences on the “personal”

freedom of choice

about the decision to

divorce (or to abstain to divorce) would render the agreement contrary to public order

and therefore null and void. In other words, according to such viewpoint, with

this agreement parties

envisage a contract whose object

is their legal status of married people, whereas

personal legal status is non-negotiable (some

scholars cite here the biblical example of Esau, who traded his birthright to

Jacob for a bowl of lentil soup!).

I spent a lot of

energy and time in my articles and books trying to give evidence that this assumption is basically

wrong, as it makes confusion

between:

(i)—on one side—an

agreement in which a party would theoretically pledge not to divorce (or not to ask legal

separation), as well as to

divorce (or to ask legal separation), which would be surely against ordre public, and

(ii) an

agreement—on the other

side—in which parties only

provide for patrimonial consequences of the (possible) decision to divorce.

Moreover, the Italian legal system provides for examples of pre-emptive agreements on

the patrimonial

consequences of a new status.

Therefore in Italy (as everywhere in the world), marriage contracts—which, according to the Civil

Code, can be concluded before

the marriage—deal with patrimonial consequences of the new prospective status

of married people (distribution of assets acquired by spouses before or

after the marriage, making a choice among community of acquests, general

community of all goods, separation of assets, etc.); so, why on earth an agreement on future

consequences of another possible change of status

(divorce) should be deemed illegal?

A donation between future

spouses can be made dependant

on the prospective marriage (see article 785

of the Italian Civil Code), what means that an event consisting in the

alteration of a personal status (from

single to married) can influence property right

consequences of a contract (such as a donation). Why shouldn’t we apply

the same rule to the very similar situation in which we have another alteration

of a personal status (from married to

divorced)?

I use to say as

well that the above mentioned case law of our Supreme Court is “educationally harmful,” because it engenders the false idea that among

spouses “pacta non sunt servanda” (agreements can be broken). Actually, it happens very often that a spouse “feigns” to agree with the other in

the framework of the legal separation process, with the mental reservation to re-open the discussion

(and to set forth new

claims) three years after, during the divorce proceedings.

However, I would

like to conclude this presentation with some more optimistic notes.

Actually, in recent times many scholars declared to subscribe my viewpoint,

deeming prenuptial agreements in contemplation of separation and/or divorce

valid and enforceable, whereas some judicial decisions are starting to overturn the “traditional” case law.

For instance, in 2012 a decision by my

Court (the first one of this kind in Italy) stated that agreements

reached by married couples at the moment of their separation are valid and

enforceable also as far as their provisions in contemplation of divorce are

concerned. Therefore, the President

of the Court of Turin denied

to allocate alimony lite pendente to a woman who had claimed this money from

her husband at the moment of the start of a litigation on divorce, whereas she had given up to any such pretensions (explicitly

mentioning the case of future divorce) in the agreement she had made with her

husband during the process of legal separation three years earlier.

But a new wind is blowing also in the Supreme Court.

Among the many

cases, I would like to make here reference to a decision in which, already thirty years ago,

the Court decided that a postnuptial

agreement of an

American couple, although contrary to Italian domestic public order, was not against the

Italian international

public order and therefore was enforceable in Italy (see Cass.,

3 maggio 1984, n. 2682).

Many years later,

in 2012, the Italian Supreme Court of

Cassation ruled that the “traditional” case law was not applicable to a situation in which an Italian

couple had agreed—just

one day before the

marriage—that, in case

of divorce (or of legal separation), the wife would convey to her prospective husband the property of a flat of hers, as a compensation for expenses he had made in

order to restore another

flat of the same woman (see Cass., 21 dicembre 2012,

n. 23713).

In 2013 the same Court decided that two fiancés can agree that the sum of money that one of them has lent to the other,

can be claimed back

only if their

future marriage will end

with a legal separation (see Cass., 21

agosto 2013, n. 19304).

In both such cases

the Court claimed that these decisions would not overturn the “traditional” viewpoint, because

“prenuptial agreements in contemplation of divorce” could be considered only

pre-emptive agreements concerning

maintenance obligations or spousal support (alimony). Of course this rationale is flawed, as what pertains to the essence of

prenuptial agreements in contemplation of divorce is the fact to agree on

pecuniary consequences of divorce, regardless of the nature and scope of such

consequences: whether conveyance of real estates, or delivery of any

kind of goods, or return of money to lender, or reimbursement of expenses, or

payment of alimony, and so on.